|

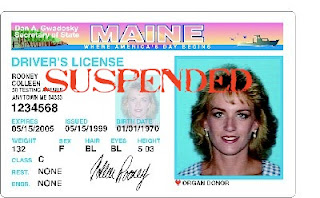

| I love her hair in this picture |

The Bad News: Penalties for those convicted of operating after suspension or revocation can be harsh!

Maine has some pretty bad law on driving after suspension or revocation. Fist off, it's easy to get your driver's license suspended in Maine. Not paying a fine, conviction for other driving offenses, accumulating points, or just changing your car insurance coverage can all result in suspension. Even after you fix the problem that got you suspended, your license will not be restored until you pay a "reinstatement fee" of $50 to the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. That's $50 for every suspension, so people with a late fine, lapsed insurance and a speeding ticket or two can be into hundreds of dollars pretty quick. That fee can leave a 15 day suspension in effect for years. To make matters worse, a suspension notice letter should be sent, but State mail does not get forwarded. If you moved, and have not update the address on your license, you won't get the notice and you might not know about any of this until you get pulled over.

The penalties seem pretty minor at first: A first OAS has a mandatory $250 fine, a second offense is $500 and a third is $750. The problem is that, if you plead guilty, the court will send the Bureau of Motor Vehicles notice of the conviction and BMV will suspend your license again for 60 days, maybe more if you have prior suspensions. Once you have three convictions for operating after suspension, or certain other offenses within a 5 year period, you can become classified as a Habitual Offender (HO) and your license will be revoked for three years.

If you drive after revocation, you are subject to mandatory minimum penalties which include incarceration for 30 days to two years depending on your priors. An HO driver who is intoxicated, eludes police, passes a road block or exceeds the speedlimit by 30 mph or more can be charged with "Aggravated operating after habitual offender revocation" and the minimum incarceration ranges from 6 months to 5 years!

The Good News: A lawyer can defend these cases.

There are ways to fight these cases. If a traffic stop led to charges, the prosecution must prove that the traffic stop was legal. Pulling someone over on a hunch that they are suspended, or because the car looked suspicious, probably is not enough. An illegal traffic stop could lead to the exclusion of all evidence discovered as a result of the stop.

The state also must prove that the defendant operated the vehicle, and under many circumstances, operation can be an issue. Often, police will find a parked car and form the opinion that a suspended suspect drive to that location. I have seen a few cases recently where an officer saw someone driving around town. The officer claims to recognize the car or driver and believes that the person is suspended. The officer then arrives at the person's home a day or two later to summons them for OAS. The question in any of these cases becomes whether the State can prove that the suspended person operated the car on the prior day.

Even if the stop was good and operation is clear, the question is was the driver properly suspended? The fact that the license is suspended or revoked is not enough to prove the case. The law requiers that one be properly notified of their habitual offender, or suspension status; it does not require proof that you actually received the notice as long as it is sent to the correct place. Notices often go to the wrong address. BMV may have multiple addresses on file and send the letter to just one, the court may send fine payment suspension notices to whatever address they happen to have in the file without ever checking the BMV address, police report addresses for the driver may differ from the court and BMV address and might be disregarded by both agencies. Other issues arise where prior convictions are alleged. The law only counts certain convictions as priors and those can only count against if the process that lead to conviction conformed with your rights to counsel and to a jury trial.

Figuring these issues out requiers meeting with a lawyer who knows the laws, knows the defenses, can make sense of your driving history report, and can fully investigate all information that might have an impact on the case. Don't think that an OAS of HO charge is always an open and shut case. A large percentage of cases can be defended in some way. Pleading guilty is great way to guarantee a conviction and another round of suspension or revocation.